Code

if (!require("pacman")) install.packages("pacman")Loading required package: pacmanCode

pacman::p_load(haven, DescTools, knitr, kableExtra, ineq, ggplot2, formatdown, tidyverse, WDI, latex2exp, stargazer, lmtest, sandwich)Lecture 7: Module 2-Education

Harounan Kazianga

Oklahoma State University

Spring 2024

Loading required package: pacmanEducation and health are important objectives of development

Education and health are also important components of growth and development – inputs in the aggregate production function

Universal primary school attendance a stated goal by many governments and development agencies.

Increasing educational attainment is believed to be one of the most effective ways of tackling poverty

At the micro level, several studies link education and individual earnings

At the macro level, pioneering work found a strong link between economic growth and human capital (e.g. Mankiw et al. 1992; Lucas, 1988) recently.

Enrollment low but varying across countries

Wide gap between rural and urban areas

Wide gap between boys and girls

Education and health are investments in the same individual

Greater health capital may improve the returns to investments in education

Health is a factor in school attendance

Healthier students learn more effectively

A longer life raises the rate of return to education

Healthier people have lower depreciation of education capital

Greater education capital may improve the returns to investments in health

Public health programs need knowledge learned in school

Basic hygiene and sanitation may be taught in school

Education needed in training of health personnel

In what ways to do governments and NGOs intervene in the areas of primary and secondary education?

How do education policies fit into larger development strategies?

How do education policies alter people’s opportunities and constraints?

By altering the menu of options for purchasing or obtaining education,

where options are defined by

-location, type, quality, language, schedule, admissions standards or eligibility criteria

fees, scholarships, conditional transfers

education promotion campaigns

Households are directly affected by education policy reforms if their children are enrolled in the affected schools either before or after the reform.

We will need to study:

School enrollment decisions

Governance and the quality of teaching and learning

Direct and indirect impacts of schooling

Market and institutional failures in education provision

The differentiated effects of education policy reforms

A household sends a particular child to school in a given year if the household’s decision makers expect the private benefits of doing so to outweigh the private costs, including the costs of financing the investment.

What kinds of benefit might parents derive from sending children to school?

What kinds of costs might parents associate with sending a child to school?

Why might some parents perceive lower returns or higher costs of schooling than others?

Why might some parents perceive that the returns to schooling girls are lower or the costs higher than for boys?

What kinds of policies might be useful for getting more children into school?

What do we learn from empirical evidence regarding the policies that might be effective for getting more children into school?

Number and location of schools

Content and language of instruction

Quality of teaching

Comfort and security

Fees and contributions

Scholarships, school meals, conditional cash transfers

Promotion campaigns

Efficiency, waste and corruption

Let \(0 \leq E^{D} \leq 1\) be the average levels of education desired by households (demand for education)

Let \(0 \leq E^{S} \leq 1\) be the average share of child time for which a school space is available (supply of education)

Demand for education depends on education price (\(P\)), (child) wage (\(w\)), and parents income (\(y\)) \[ E^{D}= \eta \left\{P+w \right\}+\theta y \]

\(\eta <0\) is the price elasticity of demand for schooling, and \(\theta>0\) is income elasticity of the demand for schooling.

Supply of education (spaces in schools) depends positively on its price (\(P\)) and negatively on its costs (\(c\)).

\[ E^{S}= \varepsilon p+\varphi c \]

Subsidy \(0\) \(\leq\) \(V\) \(\leq\) \(1\) : which lower the price of school that households pay

Conditional income transfer \(0\) \(\leq\) \(B\) \(\leq\) \(1\) : transfer is made conditional on the child attending school

Unconditional income transfer \(0\) \(\leq\) \(T\) \(\leq\) \(1\) : changes the ability to pay for school but does not require that the child attend school

School costs subsidies \(S\)

Demand and supply equations:

No government interventions is equivalent to \(V=S=B=T=0\)

Solve for \(P\) and \(E\):

\[ P^{*}=\frac{\varphi c-\eta w-\theta y}{\eta-\varepsilon} \]

\[ E^{*}=\frac{\eta \varphi c-\varepsilon \eta w-\varepsilon \theta y}{\eta-\varepsilon} \]

Equilibrium level of education is: \[ E^{*}=\varepsilon P^{*}+\varphi c \]

The first term is positive if \(P^{*}>0\), but the second term is negative

Hence positive equilibrium price is necessary but not sufficient to ensure positive education investments in the absence of government interventions.

\[ \frac{\partial E^{*}}{\partial S}=\frac{- \eta \varphi c}{\eta-\varepsilon}>0 \]

The equilibrium rises unambiguously with costs subsidies.

Unconditional cash transfers: \(T>0\), and \(S=V=B=0\)

\[ \frac{\partial E^{*}}{\partial T}=\frac{-\varepsilon \theta y}{\eta-\varepsilon}>0 \]

This is positive.

Most effective when: school demand is income elastic but not price elastic and school supply is price elastic so that more spaces can be added without raising schooling price quickly.

Conditional cash transfers: \(B>0\), and \(T=V=S=0\)

\[ \frac{\partial E^{*}}{\partial B}=\frac{\eta \varepsilon w}{\eta-\varepsilon}>0 \]

The effect is positive, reflecting a substitution effect away from child labor and toward schooling.

For some households income increases, but for other households income decrease as child time is allocated away from labor

If income effect is positive, then both income and substitution effects reinforce each other

If income effect is negative then it works to offset the substitution effect, but overall effect will still be positive if the income effect is small enough.

This assumes that the income and price effects apply equally to all children in the family, but:

Akresh, de Walque and Kazianga (2024) use experimental data to show that:

Conditional cash transfers most effective at getting parents to invest in outcomes/children they normally would not (“marginalized children”): girls, low ability, not enrolled at baseline, young, worse health

Conditional and unconditional cash transfer same impact for “non-marginalized” children: boys, high ability, enrolled at baseline, older, better health

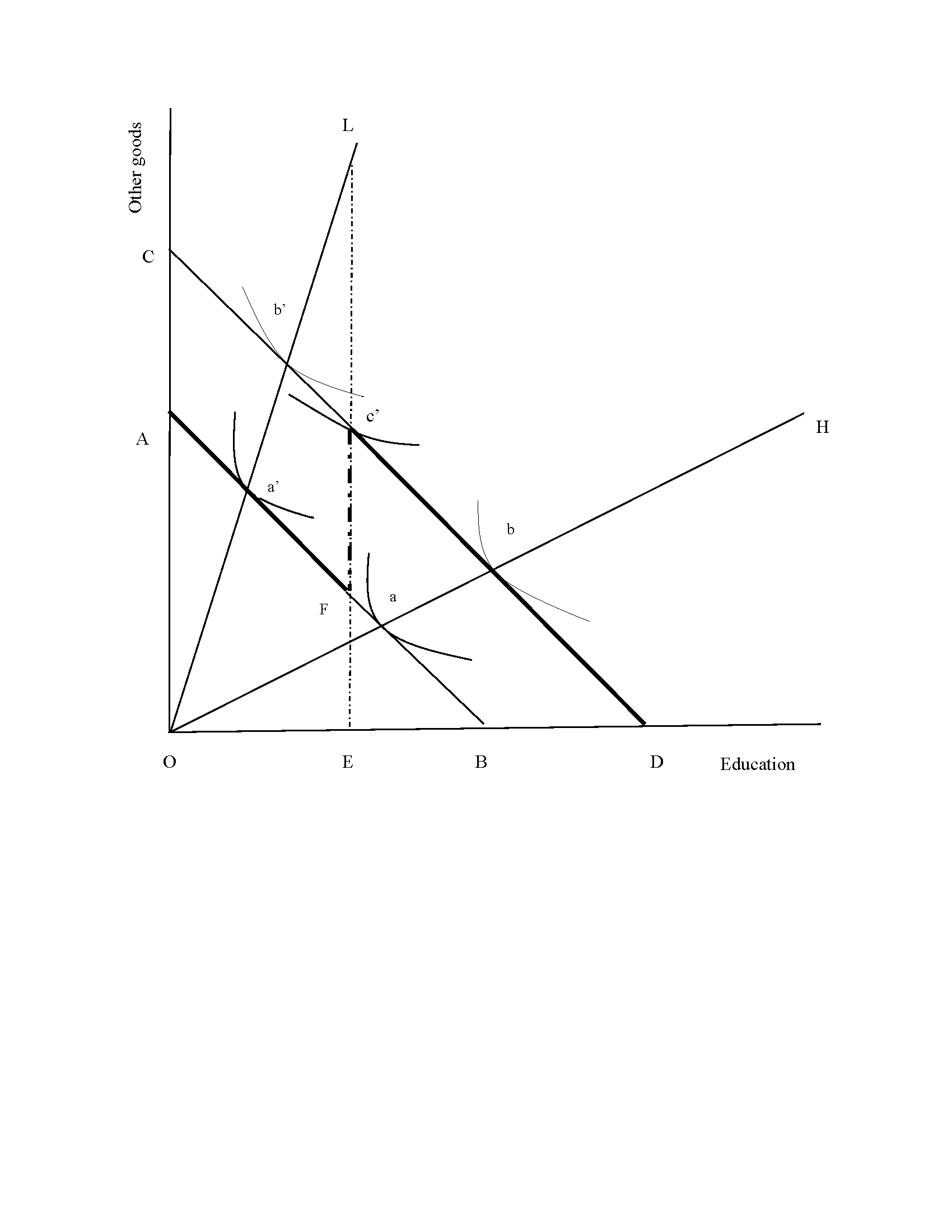

In figure @EducationFig1 :

Marginalized child = one who does not enroll or has a lower tendency to enroll in school absent an external intervention

Non-marginalized child is one that the household would be more likely to enroll

Examples of “marginalized children”: Girls; Not enrolled at baseline; Younger children (due to late start)

Also low ability children: evidence at baseline that households invest strategically in more able kids (Akresh, Bagby, de Walque, and Kazianga 2012)

For non-marginalized children, conditionality of CCT is not binding, so conditionality does not induce any change in behavior. CCT is equivalent to UCT as both shift up household budget constraint and operate through income effects

For marginalized children, conditionality can change behavior as parents enroll these marginalized children and make sure they attend at least 90% of the time

Predictions (testable)

CCTs increase education more for marginalized children than UCTs

UCT and CCT interventions have similar effects on the education of non-marginalized children

Economists and policy makers are often interested on what happens to education when circumstances change suddenly

For natural reasons: diseases, drought, flooding, etc

For man-made reasons: wars, displacements, etc.

The subject has been researched extensively

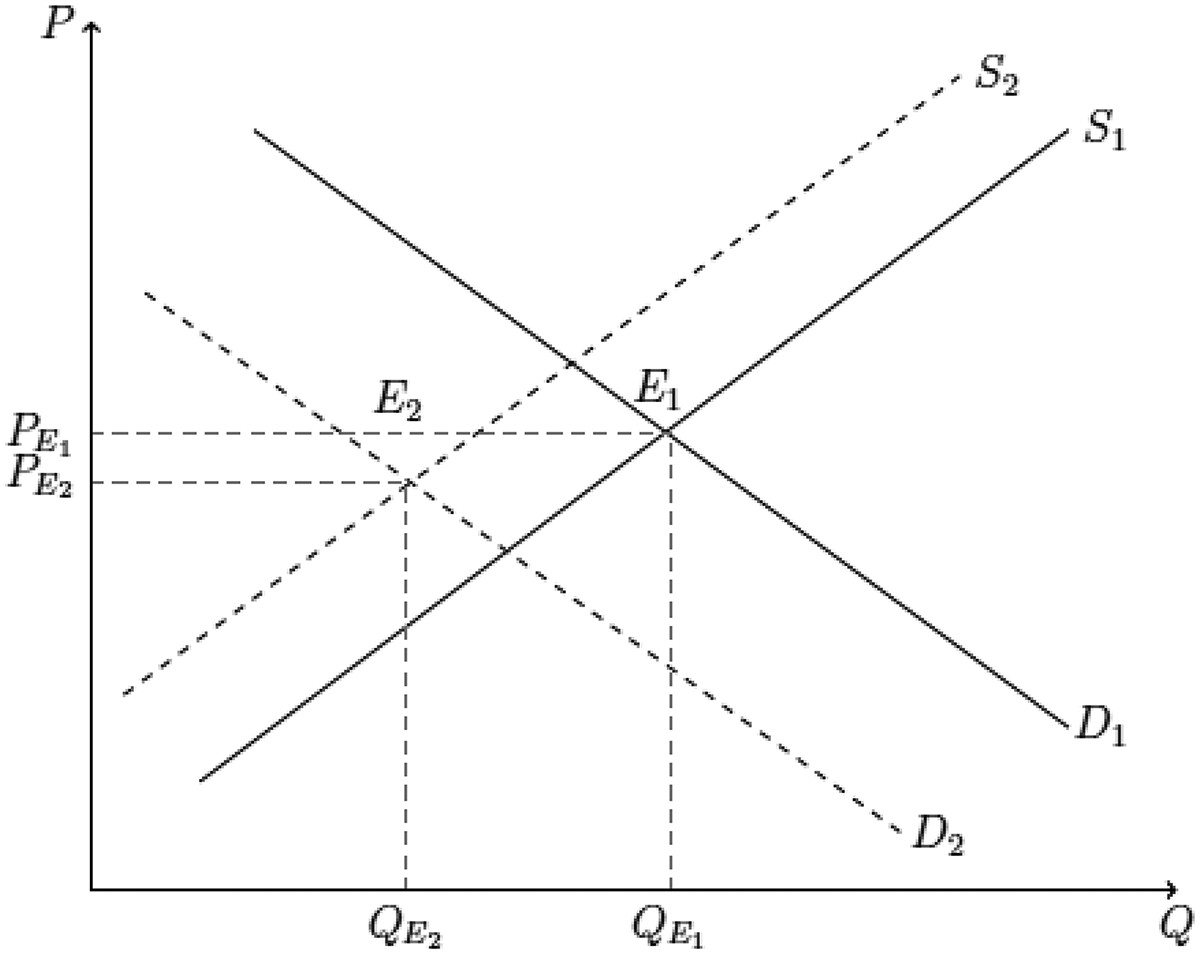

Initial supply and demand of education is \(S_1\) and \(D_1\), with an initial equilibrium at \(E_1\), and the number of children in school at \(Q_{E1}\).

Destruction of schools (because of the bombing) and displacement of teachers shift the the supply of education services to \(S_2\).

Population displacement and safety concerns mean that fewer children are sent to school, thus the demand for education shifts from \(D_1\) to \(D_2\).

The new equilibrium is at \(E_2\) with number of children in school at \(Q_{E2}\)

Remark that $Q_{E2} < \(Q_{E1}\), so there are fewer children in school because the bombing campaign

Read and prepare a short presentation (10-15 minutes) of these papers (posted on Canvas). Be specific on supply side and demand side factors, and income and price effects.

Group 2: Kazianga and Makamu (2016)